« The Ingress Protection Rating | Main | Thunderbolt 4 and other tech issues »

January 5, 2022

On Image-Stabilizing Binoculars

If you use binoculars on the job, or anywhere else, you simply have to check out the image-stabilization kind. It makes a HUGE difference. Let me explain why and how.

A good set of binoculars is often part of the gear used on the job or in the field, helping with surveys, surveillance, assessments, exploration, search & rescue and more. And a set of binoculars is almost standard equipment for anyone into wildlife observation or just generally getting a closer look at scenery or points of interest.

For all those reasons almost everyone has a set or at least has used a set, and thus is familiar with the one inevitable problem with binoculars — holding them still enough to actually see what you’re looking at. You can get a closer look with binoculars via the 7x to 12x magnification that the vast majority of them offer, but due to the inevitable slight jitters that come with holding binoculars even by the most steady-handed individuals, it’s frustratingly difficult to actually focus on something.

That’s because the human eye has different kinds of vision. While the full viewing angle of human vision is around 210 degrees, the visual field is more like 120 degrees or so, the central field of vision an even narrower 50 to 60 degrees, and what’s called “foveal vision” — the truly sharp focal point — is just one or two degrees. What does that mean?

There are various definitions of those different fields of vision, but it generally boils down to this: while the design of the human eyes and their placement in the human head technically offers a very wide viewing angle between both eyes, what we actually comprehend falls within a much narrower angle. Our “peripheral” vision is mostly limited to registering movement. We can tell that there is movement, but not what it is. The context we’re in may add information: on a highway the movement is likely a another vehicle and walking down the street it’s likely another person, but in order to verify that we need to move our eyes to take a closer look, i.e. bring that movement within a narrower viewing angle.

The more information we need for the brain to actually identify objects and how they fit in, the narrower the required viewing angle. Movement and light intensity registers within the full viewing angle, but for us to know what something really is, it must be within a much narrower angle. In familiar settings we often know what something is without actually looking at it. But our eyes continuously dart around to “bring things in focus” so we really and truly “know” what something is.

To illustrate this, try this experiment: Focus on just a single letter in what you are reading right now. While maintaining that focus on that one single letter, can you tell what the letters to the right and left of it are? Those immediately to the right and left you probably can, and you can likely tell what the word is, but without deviating the focus from that one letter, can you tell with certainty what the letter three or four positions to the left or right is? Without moving the pinpoint focus on that one letter, and without backing into it by knowing what the word is, you can’t.

That is because for us to fully see and comprehend something, it must fall into the sharp central spot of our foveal vision. And herein lies the problem with binoculars. The foveal viewing angle is so narrow that even the slightest movement makes our sight shift away from that focal point we need to truly see and comprehend. To illustrate, try reading on your smartphone while you shake it even just a bit. You can’t, at least not easily. And while binoculars magnify and bring us closer to objects, they also magnify that shaking — the very slightest movement shifts things out of our foveal vision and thus out of really seeing, understanding and comprehending a thing.

Try using a set of binoculars when you’re a passenger in a moving car. Try focussing on something with binoculars from a moving boat. Not possible. Even sitting or standing completely still, you can see that bird or deer or detail in the distance, but can you really “see” it and concentrate on it? You can’t. It’s what makes it difficult to look at stars or the moon through a tripod-mounted telescope: their even greater magnification means that even the inevitable slight touch of your head against the eye piece jitters what you’re looking at out of your foveal viewing area.

Enter image stabilization.

Advanced cameras use various methods of image stabilization to get a sharp picture even while being held with an unsteady hand or while shooting a moving object. The two primary methods used in cameras are “digital” and “optical.” The former usually refers to changing the camera settings to shorter exposure, the latter to camera sensors measuring the jitter and counterbalancing the lens to stabilize the image.

Cameras have increasingly better image stabilization. But binoculars, being purely optical devices, have none. And that’s why even the best binoculars are often useless unless they are mounted on a tripod. You can bring things close, but you can’t actually see — process and comprehend — detail.

But image stabilization is available in binoculars, and it makes all the difference in the world. It comes as little surprise that even though optics specialist Zeiss introduced image-stabilization in binoculars some three decades ago, it’s traditional camera makers, such as Canon, that are at the forefront in image-stabilized binoculars.

I don’t know what the overall market share of image-stabilized binoculars is compared to standard binoculars, but it must be small enough to fly under the radar of most. I’ve had binoculars since the late 1960s, but even when I bought my most recent set a couple of years ago I had no idea that image-stabilized ones even existed. Maybe the higher cost has something to do with it. But I did discover them and now have a Canon 12x36 IS III binocular with advanced optical image stabilization built in. What a difference! Like night and day.

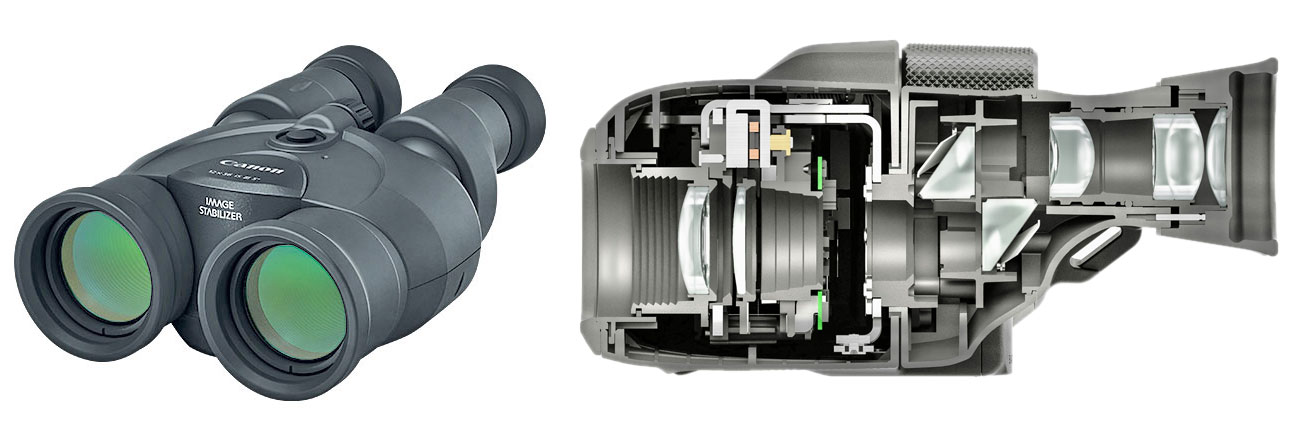

Here’s what the Canon 12x36 IS III looks like (left), and the complex stabilization mechanism that’s inside Canon binoculars.

After decades of accepting the inherent limitations of standard binoculars as just the way things are, image-stabilization changes everything. Instead of seeing birds or deer from close-up but not actually “seeing” and being able to concentrate and process what you're seeing, with image-stabilization it's like watching things on a movie or TV screen.

The video below was taken by using a smartphone adapter hooked up to the Canon 12x36 IS III. The video starts out with the normal shaking that comes with holding binoculars with 12x magnification. Then the stabilization button is pushed for comparison.

controls="controls"/>

The difference is tremendous. Just push that button and the Canon's anti-shake technology does the rest. Let the button go and stabilization turns off (to save battery). You can use such stabilized binoculars from a boat or any other moving vehicle. It’s one of those things that you have to see and experience yourself. The absence of shaking means what you’re looking at stays within your foveal vision, the sharp central vision that makes us humans see, experience and comprehend. And that’s what it’s really all about.

How different are stabilized binoculars? While most conventional sets look more or less the same, image-stabilized ones look distinctly different because instead of just lenses, IS binoculars also house the stabilization mechanisms and the batteries to drive it. So it’s a bit like the difference between an old film SLR camera and a new digital one that includes all the electronics and the batteries.

Overall, if you use binoculars on the job and are often frustrated by their inherent limitations, try one with image stabilization. You’ll instantly become a believer. — Conrad Blickenstorfer, January 2022.

Posted by conradb212 at January 5, 2022 10:43 PM