Slates or tablets are computers without a physical keyboard. The entire computer is built into a tablete-like enclosure that is as thin and handy as possible.

Since they don't have a physical keyboard, tablets use touch and often also passive or active digitizer pens for input. In early pen computers, the pen was used both to replace the mouse or joystick for navigation, and sometimes also to actually enter text.

Tablet computers may use a passive digitizer that can be operated with a stylus or even a finger. Active digitizers (which became required in 2001 by Microsoft's Windows XP Tablet PC Edition) use an electromagnetic digitizer with a special pen. Some pen tablets can automatically switch between passive and active digitizers. All pen tablets have on-screen keyboards or you can, of course, connect a standard keyboard. And since the advent of the Apple iPhone and iPad, more and more rugged tablets use capacitive touch either by itself, or in conjuction with a stylus or pen.

Tablets are perfect for many field applications where low weight and maximum portability are crucial. Some ruggedized tablets weigh barely more than two pounds. Others are heavily sealed and ruggedized and can be used in almost any environment.

A variant of the "pure" tablet computer is the notebook "convertible." Convertibles are standard notebooks with displays that twist and then lay down flat on top of the keyboard/system unit, converting the notebook into a slate computer, albeit a relatively heavy one.

A variant of the "pure" tablet computer is the notebook "convertible." Convertibles are standard notebooks with displays that twist and then lay down flat on top of the keyboard/system unit, converting the notebook into a slate computer, albeit a relatively heavy one.

Today, with hundreds of millions of tablets sold, ruggedized tablets and Tablet PC convertibles are increasingly successful in many industries, in business, and even with consumers who need something tougher and more durable than mass market tablets.

A bit of tablet computer history

In the late 1980s, early pen computer systems generated a lot of excitement and there was a time when it was thought they might eventually replace conventional computers with keyboards. After all, everyone knows how to use a pen and pens are certainly less intimidating than keyboards.

Pen computers, as envisioned in the 1980s, were built around handwriting recognition. In the early 1980s, handwriting recognition was seen as an important future technology. Nobel prize winner Dr. Charles Elbaum started Nestor and developed the NestorWriter handwriting recognizer. Communication Intelligence Corporation created the Handwriter recognition system, and there were many others.

The pen computing hype of 1991/92

In 1991, the pen computing hype was at a peak. The pen was seen as a challenge to the mouse, and pen computers as a replacement for desktops.

Microsoft, seeing slates as a potentially serious competition to Windows computers, announced Pen Extensions for Windows 3.1 and called them Windows for Pen Computing. Microsoft made some bold predictions about the advantages and success of pen systems that would take another ten years to even begin to materialize. In 1992, products arrived. GO Corporation released PenPoint. Lexicus released the Longhand handwriting recognition system. Microsoft released Windows for Pen Computing. Between 1992 and 1994, a number of companies introduced hardware to run Windows for Pen Computing or PenPoint. Among them were EO, NCR, Samsung (the picture to the right is a 1992 Samsung PenMaster), Dauphin, Fujitsu, TelePad, Compaq, Toshiba, and IBM. Few people remember that the original IBM ThinkPad was, as the name implies, a tablet computer. And few know that Samsung was a factor in tablets even back then.

The crash of 1993

The computer press was first very enthusiastic about tablet computers operated with a pen. But the media quickly became very critical when pen computers did not sell as well as anticipated. The press measured pen computers against desktop PCs with Windows software and most of them found pen tablets difficult to use. They also criticized handwriting recognition and said it did not work.

After that, pen computer companies failed. Momenta closed in 1992. They had used up US$40 million in venture capital. Samsung and NCR did not introduce new products. Pen pioneer GRiD was bought by AST for its manufacturing capacity (but sort of lives on even today as GRiD Defence Systems in the UK). AST stopped all pen projects. Dauphin, which was started by a Korean businessman named Alan Yong, went bankrupt, owing IBM over $40 million. GO was taken over by AT&T, and AT&T closed the company in August 1994 (after the memorable "fax on the beach" TV commercials). GO had lost almost US$70 million in venture capital. Compaq, IBM, NEC, and Toshiba all stopped making consumer market pen products in 1994 and 1995.

The mid and late 1990s

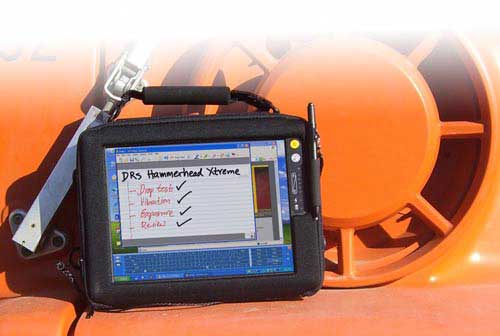

By 1995, pen computing was dead in the consumer market. Microsoft made a half-hearted attempt at including "Pen Services" in Windows 95, but pen computing had gone away, at least in consumer markets. It lived on in vertical and industrial markets. Companies such as Fujitsu Personal Systems, Husky (bought by Itronix in 2000), Telxon (bought by Symbol in 1998), Microslate, Intermec (bought by Honeywell in 2012), Symbol Technologies (bought by Motorola in 2007), Xplore (taken over by Zebra in 2018), and WalkAbout (bought by DRS in 2005) made and sold many pen tablets and pen slates. A primary problem was that companies making pen computers had to create their own pen drivers for every new model. Compatibility was a big issue, as was the high cost of pen computers.

2002: Microsoft reinvents the pen computer

That was, however, not the end of pen computing. Bill Gates had always been a believer in the technology, and you can see slate computers in many of Microsoft's various "computing in the future" presentations over the years.

Once Microsoft reintroduced pen computers as the "Tablet PC" in 2002, slates and notebook convertibles made a comeback, and new companies such as Motion Computing (bought by Xplore in 2015) joined the core of vertical and industrial market slate computers specialists.

The primary reason why the Microsoft-specification Tablet PC is reasonably successful whereas earlier attempts were not has two reasons. First, the technology required for a pen slate simply wasn't there in the early 1990s. And second, the pen visionaries' idea of replacing keyboard input with handwriting (and voice) recognition turned out to be far more difficult than anticipated. There were actually some very good recognizers that are still being used today, but they all require training and a good degree of adaptation by the user. You can't just scribble on the screen and the computer magically understands everything. With the Tablet PC, Microsoft downplayed handwriting recognition in favor of "digital ink" as a new data type. This was a very wise decision.

2006 brings the "Ultra-Mobile PC"

During 2005 and even earlier, Microsoft had been hinting at tablets smaller

and simpler than even the smallest Tablet PC slates. Such tablets were

supposed to cost little, 500-700 dollars perhaps, and represent a "back to

basics" move -- computing for everyone, everywhere.

In early 2006, a cleverly managed rumor campaign, led by a Flash site

hinting at a mysterious little device called "Origami," was culminated by

the release of the "Ultra-Mobile PC," or UMPC, at the CeBIT show in Hanover, Germany.

The UMPC turned out to be a small tablet with a 7-inch screen, running the

full XP Tablet PC Edition, but using a passive digitizer. To make that work,

a set of special touch utilities are included. Not much hardware was shown,

and none was initially available. See our intro to Origami

and our much more detailed analysis of the

Microsoft UMPC platform.

Around that time, Intel researchers, ever interested in exploring new markets for their chips, came up with what they called the "Mobile Clinical Assistant" reference platform, or simply MCA. This tablet design had an integrated carry handle and was first implemented by tablet pioneer Motion Computing.

2007: Vista, UMPCs, and MIDs

When Microsoft Windows Vista arrived in early 2007, Microsoft decided to include all pen functionality rather than offering a separate version as it had done with the Windows XP Tablet PC Edition. We've reviewed several slates with Vista and Microsoft did a good job seamlessly integrating all the pen options.

In the meantime, Microsoft had also introduced the Ultra-Mobile PC, or UMPC, platform in March of 2006. Microsoft's described the UMPC as "a device-like computer that is small, mobile, and runs the full Windows operating system. The UMPC goes anywhere and does anything that your current computer can do." The UMPC was initially conceived as a small, inexpensive slate with a touchscreen, but the concept didn't catch on due to low performance and higher than expected pricing.

In May of 2007, Microsoft loosened the design description to "any portable computer running full Windows with a screen size of 7 inches or smaller." Intel announced its own Intel Ultra Mobile Platform 2007 based on low-power Intel A100 and A110 processor designed to drive both UMPCs and yet another category, Mobile Internet Devices or MIDs. MIDs did not necessarily have to run standard Windows. Both the UMPC and the MID platforms seemed naturals for handheld rugged devices and we hoped to see many interesting designs.

2008: The return of touch

With the hugely successful iPhone, Apple once again changed everything. The iPhone's sleek and intuitive capacitive multi-touch interface redefined touch screens and what they can do, and all of a sudden everyone else was trying to follow suit. We saw touch screens in regular consumer notebooks again, and even in desktop machines. In rugged machines there were more and more "dual touch" systems that used both touch and an electromagnetic pen. The Tablet PC never really caught on, in part due to technological issues and in part due to Microsoft's inconsistent attention to the platform.

2009/2010: Tablet hype

Multi-touch continued to gather momentum, with many manufacturers offering some sort of multi-touch capabilities in notebooks, tablets and even desktops. The newly released Windows 7 integrated touch and multi-touch capabilities. Implementation was often clumsy, which showed the difficulty of scaling up the super-smooth operation of the Apple iPhone. There were rumors of a new Apple slate device all year, and came to a fever pitch at the 2009 CES in Las Vegas where numerous tablets and tablet concepts were shown. Microsoft had been expected to make some sort of tablet announcement, but, apart from CEO Steve Ballmer briefly showing an HP concept, nothing happened.

A few days later, however, Apple announced the iPad, a sleek 1.5-pound slate intended to fit between an iPhone and a regular notebook computer. The device was clearly built from the iPhone up, and not from a notebook down, and so was expected to primarily address the needs of those who had begun using their smartphones as notebook replacements but would like a larger screen. Microsoft, in the meantime, closed its Tablet PC blog and, for all practical purposes, their Tablet PC experiment was over.

2010, in the meantime, became the year of the Apple iPad. Three million were sold in the first 80 day of availability, and the platform sold at about two million units a month for most of 2010. Hewlett Packard bought Palm, and with it Palm's WebOS, a well-regarded OS suitable for potential competitors to the iPad. RIM announced tablet plans, Microsoft made noises about a new tablet platform, and the Google-pioneered and Linux-based Android smartphone OS was widely seen as the most likely platform to compete with Apple.

2011: Begin of the post-PC era?

With some 15 million Apple iPads sold in 2010, it was clear that the touch tablet platform has massive potential. Analysts predicted huge media tablet sales, in part replacing netbooks, in part even standard notebooks.

Despite the success of the Android OS in smartphones (where it became the leader in 2010), tablet competition to the iPad was slow in ramping up. Samsung launched their 7-inch Tab late 2010, RIM and HP announced tablets, but Motorola got the best press with their 10.1-inch Xoom Android tablet. The biggest problem seemed that there was not much opportunity for vendors to a) differentiate themselves, and b) meet Apple's very low pricing.

By early 2011, Microsoft had still not reacted to the tablet boom, still referring to Windows 7 as a tablet solution. Motion Computing released the CL900, the first somewhat ruggedized media tablet, and Fujitsu followed with the similar Stylistic Q550. Panasonic pre-announced, to great fanfare at Dallas Cowboy stadium, a 10.1-inch Android tablet. In September, Microsoft showed a developer demo of Windows 8 with a touch-oriented "Metro" front end and support for ARM processors, albeit not in "classic" Windows 7 mode. In October, Motorola Solutions, newly separated from the Motorola "Mobility" phone business (acquired by Google in the summer of 2011), introduced a ruggedized 7-inch Android tablet, the ET1. And in November, Panasonic announced the Android-based Toughpad line of tablets.

2012: iPad continued to blaze the tablet trail

In early 2012, Apple introduced the 3rd generation iPad that set a new display resolution standard for tablets with a 2028 x 1536 pixel LCD. With tens of millions of media tablets sold, the iPad and its still struggling competition had clearly blazed the trail for the tablet form factor. The question in mid-2012 was whether it would be Android or Windows 8-based tablets that provided the primary iPad competition, and whether rugged vertical market tablets would be able to benefit from the iPad's popularity. In the Fall of 2012, Microsoft formally introduced Windows 8 and with it the Windows RT version of its Surface tablet. The Surface hardware was well accepted, the Windows RT software, written to run on ARM processors but curiously stunted, less so. For the most part, tablet makers held off on Windows 8, assuming a wait-and-see attitude.

2013: Tablets are taking over

After several years of almost complete iPad dominance, non-Apple tablets rapidly gained market share, helped by consumer and business market offerings by Amazon, Google, Samsung and others. Tablets and smartphones began to be seen as a fundamental shift, with those platforms taking over many functions previously done on desktops and laptops.

In vertical markets, tablet vendors continued to struggle with deciding whether to stay with Microsoft Windows despite slow user acceptance of Windows 8 and Microsoft's own Surface tablet hardware, or taking the risk of switching to Android. Several began offering both Windows and Android versions. Traditional tablet vendors also suffered from an onslaught of inexpensive "white box" Windows-based tablet hardware.

2014: Android still slow to take hold in rugged tablets

Consumer tablets were everywhere, selling by the tens and hundreds of millions. The iPad remained a major player, but its complete dominance was over as Android was set to repeat its success and dominant position the platform had reached in smartphones. Yet, just like with handhelds where Windows Mobile and Windows CE continued to dominate in vertical/industrial markets long after they vanished from the consumer space, the same was happening in vertical/industrial tablets.

While there were several fairly high profile Android ruggedized tablets, the majority remained Windows-based. And that despite Microsoft's own limited success with its Surface tablets, and despite the mixed reception of Windows 8/8.1. Some vendors offered both platforms. Others started with Android, but then added Windows tablets.

In mid-2014, we saw the first commercially available tablets with advanced capactive touch controllers that allowed the use of (passive) capacitive pens with tips no larger than that of a ballpoint pen. This would prove to be a game changer.

2015: The Empire strikes back

The Windows empire, that is. While the smartphone and most of the consumer tablet markets were completely dominated by Android and Apple's iOS, Android failed to take over the industrial, enterprise and vertical tablet markets as well. Most providers of tablets in those markets offered both Windows and Android-based versions, but the momentum remained on the Windows side.

The Windows momentum was helped by Microsoft's increasingly successful entry into the tablet hardware market where its Surface and Surface Pro tablets quietly racked up sales in the several US$ billions, which was massive considering that the entire rugged mobile computing market (tablets, handhelds and laptops) only amounted to about US$4 billion in 2015.

2016: Tablet saturation

Six years after the launch of the iPad, the tablet market showed signs of saturation and maturity. Everyone who wanted/needed a tablet had one, and there was very little innovation as it was quite difficult to truly differentiate a tablet in looks, functionality and technology. Microsoft continued to show strength with their Surface tablets. There seemed no money to be made in generic white-box tablets, and the market looked primarily to high-end "Pro" versions.

Rugged tablets, by and large, had not been able to truly cash in on the massive popularity of the tablet form factor. Primary obstacles were the higher price of rugged tablets, OS fragmentation, slow progress in outdoor usability of touch, and stagnation in achieving true sunlight viewability. One bright spot were 2-in-1 hybrids, tablets with detachable tablets specifically designed to work with a particular device, and thus providing both tablet and laptop functionality.

2017: Rise of the hybrids

Tablets had become part of life, for consumers and on the job alike. Microsoft declared its latest Surface tablet a "laptop," most tablet vendors were paying much more attention to detachable/complementary keyboards that really worked with a tablet.

An ongoing problem was Windows' marginal suitability for use on tablets on the one side, and Android's clear emphasis on smartphones on the other side. As a result, Microsoft was doing surprisingly well on larger tablets (where Windows checkbox, scrollers and pulldowns were a bit easier to operate than on handhelds), while Android still wasn't anywhere near as dominant on tablets than on handhelds.

An ongoing problem was Windows' marginal suitability for use on tablets on the one side, and Android's clear emphasis on smartphones on the other side. As a result, Microsoft was doing surprisingly well on larger tablets (where Windows checkbox, scrollers and pulldowns were a bit easier to operate than on handhelds), while Android still wasn't anywhere near as dominant on tablets than on handhelds.

2018: Bigger (but lighter) tablets, Android woes continue

As smartphones continued to increase in size, they began replacing small tablets. The new low end display size for tablets was 8 inches. Large-screen tablets (often called "pro" versions) were increasingly popular. While Android had a commanding (overwhelming really, almost everything that was not the proprietary iOS) market share in smartphone, Google's inexplicable disinterest in tablets meant that Android adoption in tablets remained much slower than in handhelds.

Another interesting development was that relatively lightweight rugged tablets were replacing older and much heavier rugged tablet designs. This trend was fueled by increasing miniaturization of electronics, the replacement of hard disks with tiny and far less vulnerable solid state disks, and higher battery density. RuggedPCReview fastest rugged tablet of 2018: Zebra XSLATE L10

2019: A year of refinement

2019 was a fairly quiet year for rugged tablets, with most news limited to tech upgrades due to Intel's rapid pace of ever more powerful processor generations. Microsoft remained fairly successful with its (non-rugged) Surface tablets for which a number of rugged cases were available (

see MobileDemand's xCases for Surface). Google remained indifferent about Android tablets, fully concentrating on handhelds. RuggedPCReview fastest rugged tablet of 2019:

DT Research DT301X.

2020: COVID-19 and Android migration

2020, overall, stood under the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic. Dramatically increased caution, testing, access control, identification, biometrics and more meant much demand for tablets both for use in home offices and home schooling, and also in specially equipped versions for corporate and medical settings. In addition, we saw rugged Android tablets become part of the migration from Windows CE/Windows Mobile to Android.

2021: Recovery but ongoing COVID-19 issues

After having seen contractions in many tech industries in 2020, 2021 saw cautious and then accelerating recovery fueled by backlog and increased use of mobile technology for COVID-19 related applications. Supply chain issues meant delayed availability of announced products as well as shortages of chips and modules, at times resulting in dropping of features. Intel's 11th generation of Core processors turned out to be a big success and move forward both in rugged tablets as well as rugged laptops. Most larger tablets continue to be Windows-based.

2022: Cautious post-pandemic stirrings

Supply chain and component shortage issues continue to bedevil the industry, though the worst is behind. Most premier rugged Windows tablets take advantage of Windows 11 and the capabilities brought by Intel's excellent 11th generation of mobile Core processors. The promise of Thunderbolt 4 remained somewhat unfulfilled due, in part, to a lack of standardization in up/downstream charging protocols. As of mid-year, Intel 12th generation "Alder Lake" had yet to make an appearance. Android adoption in professional-grade tablets was picking up some, but remained way behind where Android is on handhelds. Later in the year, we saw some interesting new products in 8-inch Windows offerings from RuggON (LUNA 3) and Durabook (R8). We also saw first-ever high-performance 10-inch Windows tablets from Juniper Systems (Mesa Pro) and others.

2023: Getting back to normal

After three pandemic years, 2023 saw a cautious return to normal, with some rugged systems industries thriving to fill the substantial backlog. On the Microsoft side, tablets benefitted from the Windows 10 to Windows 11 transition, the new OS somewhat more touch and tablet friendly, and also better able to takle advantage of Intel's 12th and 13th generation of Core processors. Emphasis was on 10 and 12-inch tablets. Given Android's great strength in the handheld device market, its relative weakness in tablets continues, with Panasonic giving up on Android for their rugged platforms entirely.

Portuguese translation of this page by Artur Weber at

https://www.homeyou.com/~edu/rugged-tablets.